What's interesting is that while high brow critics on the one hand berate the low art of Sex and the City, they also validate its success precisely because the conversation about Top Girls and its cultural implications would not be happening had Sex and the City not been the success it is. Sex and the City is a change making movie. It has changed the conversation about women and film and now its spilled into theatre. Mr. Isherwood begins his article talking about Top Girls but ends it with question about women and films.

Hollywood movies, on the other hand, have all but abandoned women’s experience as a fertile subject for entertainment. The relentless pursuit of adolescent boys of all ages seems to have taken over almost completely. I look back with nostalgia at the wealth of women who had major film careers in the 1970s and ’80s: Jane Fonda and Sissy Spacek, Barbra Streisand and Jessica Lange, Diane Keaton and Meryl Streep and Bette Midler.

Now it seems that a superb central role for a woman — as opposed to the girlfriend-foil roles taken by the ingénues of the moment, like Anne Hathaway or Katherine Heigl — comes along once a year. Increasingly they seem to be given, as if by rights, to the rangy Ms. Streep, who stars in the forthcoming film versions of “Mamma Mia!” and “Doubt.” (Both of those, incidentally, or perhaps not so incidentally, are based on stage properties.)

“Sex and the City” at least gave women’s lives, however romanticized, a foothold at the multiplex. The superb foursome of actresses who star in the film were the top girls at the box office for a glittering, attention-getting moment, relegating even Indiana Jones — still swashbuckling into his dotage, apparently — to second place.

Glass Ceiling, Meet Sisterhood (NY Times)

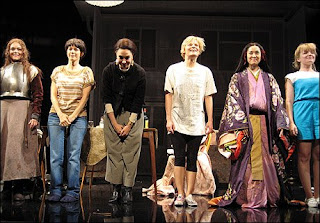

(photo: Aubrey Reuben)